Over the past 20 years, Ottawa-Gatineau sprawled the most of the 9 largest Canadian metropolitan areas.

According to analysis by data scientists at Radio-Canada, from 2001 to 2021, the population of Ottawa-Gatineau increased by 27%, while the surface area of the land used for homes grew by 50%.

(I’ll refer to “Ottawa” going forward since most of the sprawl happened on the Ontario side.)

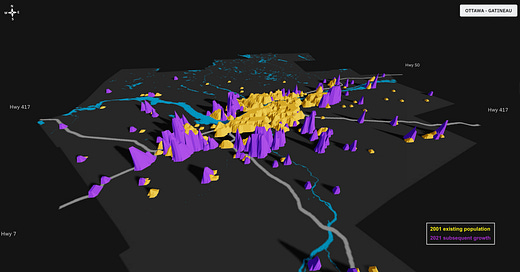

Ottawa’s sprawl took place in the purple areas in the image below. If you orient the city by the Ottawa River and the Hwy 417, you can see very strong growth in Kanata, Stittsville and Barrhaven, and steady growth in Riverside South and Orleans.

Ottawa’s population density fell by 19% — more than other Canadian metropolitan areas over the past two decades.

Car-centric design

Sprawl is what happens when we design cities around cars.

Having to drive everywhere makes us less active and healthy, and less connected to our community. It a leading cause of carbon emissions in cities.

Sprawl requires that we put in a lot of expensive roads, sewers and other infrastructure. Sprawl creates a ticking time bomb for future generations as that infrastructure will need to undergo expensive upgrades and replacements within a generation or two.

How did we get here?

Developers like building new communities. It’s predictable and profitable.

When developers can purchase remote lands and get a Council to reclassify those lands within the urban boundary (and therefore permissible for building homes), it can be extremely profitable.

And Ottawa is a city where many Councillors are happy to follow the suggestions of developers.

One Globe and Mail editorial writer kicked off a debate last year that suburbs were inevitable. People choose to live where they live.

But others have pointed out the decisions of our elected leaders means that households often have only one choice: live in the suburbs.

Decisions over 20 years

Ottawa didn’t become a sprawling city by accident. Consider the following.

Our zoning by-laws have discouraged in-fill development in existing built-up areas. Zoning requirements often make intensification “illegal” (e.g., R1 zoning that only allows single family homes), or they might make the business case simply uneconomical for developers (e.g., setbacks and height limits that prevent a builder from using the space profitably).

The taxpayers of Ottawa are heavily subsidizing suburban development. A 2021 consultant’s report reminded us that each new suburban home requires an annual subsidy of $465 per person, while each new in-fill home nets the city a surplus of $606 per person.

Families want green spaces and recreational opportunities near their homes, but Ottawa has not been providing the parks and rec centres in central areas that families would need to live in higher-density buildings.

Higher levels of government provide many financial incentives for home owners (capital gains tax exemption, a long list of home buying incentives) but few for renters.

So Ottawa has not provided real options for where we can live. Particularly for families, there is no real choice other than the suburbs.

Sprawl is not inevitable

Past does not have to be prologue.

Hamilton made a dramatic u-turn, pushing back on urban sprawl. Last year, 90% of all new home construction in Hamilton took place as intensification, in-fill and redevelopment within built-up areas — in sharp contrast to the building pattern of previous years.

What choice will Ottawa make?

Ottawa can keep sprawling.

Or Ottawa could make a similar u-turn.

Ottawa could get serious about intensifying within its existing urban boundaries. There is plenty of undeveloped land within existing boundaries. And there is a lot of underdeveloped land.

Our Official Plan says that 60% of all new development is to come through building in existing urban areas.

Will Council follow the directions of that Plan? Or will they ignore it and continue to prioritize sprawl?

All excellent points on 70-yrs of suburbanization with private capital thanks to Greber's vision and other modern planning models. I think it takes some deeper thought about how we do it. The extremes of density of non-community oriented condo towers (that is happening in downtown Ottawa and looses the 15-minute soft city ideal) vs. the non-place density of marginal areas on strodes. It would be interesting to actually go back to a garden city principles with exceptional public transit (i.e. it is free for most, with surrounding zones paying, and a congestion tax). Right now, there is commute grid lock and lack of car parking in downtown Ottawa because people only come in to their offices a few times a week and are not interested in paying for a transit pass.

So...no one wants to mention and talk about Amalgamation? Anyone? Like remember when Gloucester, Orleans, Stittsville and Kanata where their own towns?